How To Lose 3 Million Fans In One Easy Step

With just one album, Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark more or less destroyed their career. And they weren't the only ones: the early 1980s were littered with commercial suicides. Bob Stanley finds out how it all went wrong

Friday March 7, 2008

The Guardian

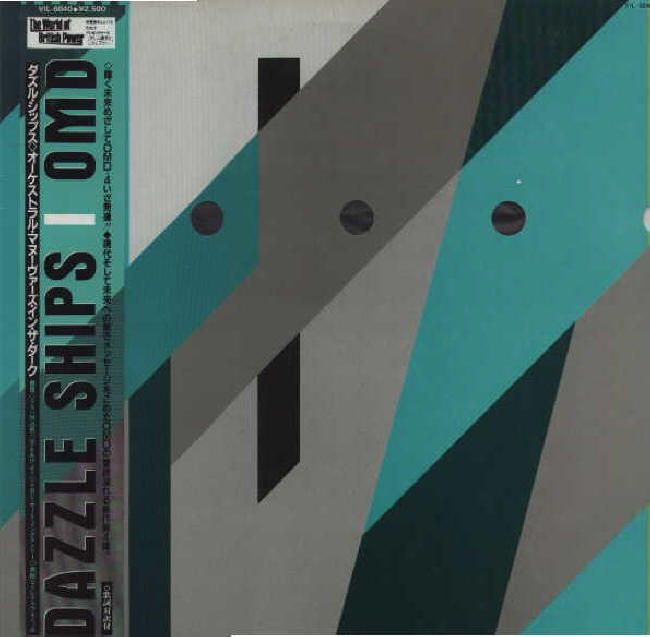

Guy Hands wouldn't allow it these days - what are these "artists" trying to do? Bankrupt the company? - but in 1983, no one batted an eyelid when a major chart band followed a multimillion selling pop album with something extremely obtuse. An album, even, that contained no obvious hits and soundtracked the cold war at its coldest. No one bought it, mind you, so Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark's Dazzle Ships came to be viewed as a heroic failure - the ultimate commercial suicide.

"Every year we'd visit American Forces Network [the broadcaster for US troops] in Germany," remembers OMD's Andy McCluskey. "There were almost a million people at [the US] Frankfurt base, it was like a colony. And we'd see the same guy every year when we went there to do an interview. So we gave him Dazzle Ships and he said, 'Wow! Gee, what a weird album. Radio Prague? Let's play it! They'll think the commies have invaded!'"

Architecture and Morality, OMD's third album, had been a monster hit following its release in 1981, with any number of potential singles. Souvenir was first out of the block and made No 3. When Joan of Arc got rave reviews ahead of the album's release, McCluskey told Smash Hits: "That's nothing. Wait until you hear the next single - it's our Mull of Kintyre." Maid of Orleans duly became another huge hit in the UK, and Germany's best-selling single of 1982.

"It sounds strange, I know, but we had been trying to change the world," says McCluskey. "It was the naive confidence of youth, the idea that music is that important. The music we made had to be interesting and different. And somehow we believed that would change the world, the way people think. So when we sold 3m albums and the world didn't change, we were scared."

The result was a bout of writers' block. It wasn't as though OMD wrote conventional love songs to start with - Enola Gay was famously about Hiroshima, Stanlow about a power station - yet Dazzle Ships took off what McCluskey calls "the sweet wrapper". For starters, the first single was called Genetic Engineering. "I was very positive about the subject! I didn't expect someone like Monsanto to come along and say, 'Fuck it, we can make money out of cross-pollination.'"

However, when Dave Lee Travis played the single on Radio 1, he said - with some gravitas - that it was about time someone in the music world stood up to the evils of tinkering with nature. "People didn't listen to the lyrics," McCluskey recalls. "I think they automatically assumed it would be anti. Generally, I was pretty dark and pessimistic. Very precious and strong-minded."

The song is still one of Dazzle Ships' more overtly commercial moments. Disembodied voices from the eastern bloc sit over recordings of time signal pips, speak-and-spell machines, wartime submarines. "It all made sense to us. We wanted to be Abba and Stockhausen. The machinery, bones and humanity were juxtaposed."

Dazzle Ships entered the charts at No 5, then dropped like a stone. Architecture and Morality sold 3m; Dazzle Ships sold 300,000. With one record, Orchestral Manoeuvres lost 90% of their audience.

"I was the ideas man, Paul Humphreys made it happen. It was a symbiotic relationship. But I'm the one who took us right to the edge of the plank. When people heard Dazzle Ships, they obviously preferred our music with the sweet wrapper on. Not a song about someone's hand being cut off by a totalitarian regime. After that, there was a conscious and unconscious reeling-in of our experimental side. We got more ... conservative."

As, of course, did the whole country. Dazzle Ships, falling between the Falklands war and the Tories' emphatic

re-election, sounded the bell for the new pop playground that the charts had become. An almost forgotten era, now lumped in with the ephemera that succeeded it- the likes of Johnny Hates Jazz - new pop was an attempt in 1981 and 82 to marry chart music to the avant garde. Incredibly, it succeeded. There was no manifesto, but the new generation - OMD, ABC, Soft Cell, the Teardrop Explodes, Dexys Midnight Runners - had lived through punk, understood its situationist leanings, and understood the real value of music. While OMD name-dropped Dancing Queen, Ian Curtis and Mies van der Rohe, ABC claimed they existed to write "a soundtrack for the 80s".

At the turn of the decade, ABC had been Vice Versa, a Sheffield post-punk unit who leaned more towards the atonal than to Abba. They were interviewed for a fanzine called Modern Drugs by Martin Fry, and got on with him so well they asked him to become their singer. After changing their name to the perfectly minimalist ABC, they sat down to write some perfectly modernist love songs: Tears Are Not Enough, Poison Arrow, The Look of Love, All of My Heart. All Top 20 hits; all soulful, well-dressed pop. Their parent album, The Lexicon of Love, defined the charts of 1982.

ABC predated OMD in their attempt to take on the preconceptions of their fanbase, and their second album, Beauty Stab, did not define the charts of 1983. The strings were gone, replaced by some tough guitars that sounded weirdly dated - sometimes like Low-era Bowie, sometimes closer to Led Zeppelin. Had it been released two years later, when guitars were voguish once more, it would have kept the ABC boat afloat. Instead, it just sounded confusing.

Like Genetic Engineering, the first single from Beauty Stab - That Was Then But This Is Now - was exhilarating and shrill, and made the top 20. The cause wouldn't have been entirely hopeless but for one line: "Can't complain, mustn't grumble, help yourself to another piece of crumble." It had perhaps been meant as a joke - it was followed by a cheesy sax break - but Roddy Frame of Aztec Camera lambasted it in an interview as embodying all that was bad in modern pop. Suddenly, the emperor's new pop clothes were revealed. The line has been a fixture in "worst lyrics" polls for 25 years, attaining the top slot in one conducted last year by BBC 6Music. Beauty Stab, like Dazzle Ships, died a quick death.

Which leads you to wonder what the hell happened in 1983. It was almost as if the country was tired of mavericks, had heard enough about unemployment figures and ghost towns and nuclear threat. They wanted glamour, in a Seaside Special way. Duran Duran had their first No 1 in 1983. Paul Young, Wham! and Howard Jones - considerably more pliable and predictable than OMD or ABC - were the year's new stars. Waiting around the corner, jacket sleeves already rolled up, was Nik Kershaw.

According to Kevin Rowland of Dexys Midnight Runners, the music industry had started to become "incredibly conservative. I was dealing with people who were much more careerist. At Mercury, by 1985, there were loads of public-school people - millions of them."

Dexys had already crashed once when, following the No 1 hit Geno, they recorded the super-intense single Keep It Part Two (Inferiority Part One). It received no airplay and failed to crack even the top 75.

"I just had something to say," says Rowland. "I was disappointed with success - we were still cramped in a minibus on hot summer days. I did not think, in any way, that Keep It was difficult. It was truthful, 100% truthful. Geno had been a No 1; I thought, if you like that amount of emotion, try this amount of emotion."

Dexys, though, had a second wind, and fought back with the million-selling Celtic soul of Too-Rye-Ay in 1982. Come On Eileen became an international No 1. They had survived and prospered. Too Rye Ay's follow-up, Don't Stand Me Down, was an astonishingly personal and beautiful record, but it became Dexys' equivalent of Dazzle Ships. The problem was it came out three years after Too-Rye-Ay.

Rowland is understandably proud. "I don't want to think about it too much because I want to think about what I'm doing now, but I remember coming out of the studio thinking, 'That's the best I can do.'"

Don't Stand Me Down emerged in a far less adventurous era than the one Too Rye Ay was released into. New mavericks on the block such as the Smiths and the Jesus and Mary Chain were entirely ignored by Radio 1. The same happened to Dexys, though it was their own fault - no single was released from the album.

"It was a stupid mistake," Rowland says. "I wanted This Is What She's Like to be the single, a 10-minute single. The manager said, 'Good idea ... or no single at all.' It was a chance to be like the groups of the early 70s, like Led Zeppelin. I thought that would be great, but I wasn't sure. There was a new guy at Mercury and he was like, 'What?' That was it. I said, we're definitely not releasing one. They [the label] went with Don't Stand Me Down for about a fortnight. Then they moved on to something else."

British eccentricity may well play a role in these crash-and-burn albums - a willingness to be contrary. Some Americans have followed gold albums with zero-sellers, but not many. Harry Nilsson's Nilsson Schmilsson contained the original lung-busting power ballad, Without You, and made him a rich man. Never one for the obvious, he gave its sequel the misleading title Son of Schmilsson and filled it with raggedly sung novelties. It contained no obvious hits, though You're Breaking My Heart, a song for his ex-wife, did stand out: ABC's "apple crumble" line hardly holds a candle to "you're breaking my heart, you're tearing it apart, so fuck you".

That was calculated self-destruction. Neil Young, having tasted fame and fortune with After the Goldrush and Harvest, famously said he would rather head for the ditch than stay in the middle of the road. And that's just what he did with Time Fades Away. Young recorded the stoned, muddy, hard-rocking album on a stadium tour to confused audiences who had never heard the songs before. No atmosphere, no acoustic balladry, just memories of getting a kicking in the schoolyard and an extended moan about LA. Young's profile duly disappeared.

Fleetwood Mac's Rumours had been recorded in trying circumstances. The sequel had the even more onerous task of following what was then the bestselling American album ever. Lindsey Buckingham assumed control of 1979's Tusk. Though it cost £1m to make - a figure that even today seems barely plausible - much of it sounded clattery, half-formed, with strange rhythmic leaps and offbeat tics. Hotel California it wasn't.

It later emerged in his girlfriend's memoirs that Buckingham had become obsessed with Talking Heads, and was desperate to make Mac relevant to a post-punk world. The problem was that even though Rumours had been all about break-ups and unfaithful lovers, it still sounded as though the roof was down and you were heading up the highway in the sunshine. Tusk was unleavened weirdness, as close to its predecessor as the Beach Boys' lo-fi Smiley Smile had been to Pet Sounds. It simply didn't cut the midwest mustard. However, like Dazzle Ships, Tusk makes a lot more sense to 2008 ears.

"The album that almost completely killed our career seems to have become a work of dysfunctional genius," says Andy McCluskey with a grin. "The reality is that it's taken Paul [Humphreys] 25 years to forgive me for Dazzle Ships. But some people always hold it up as what we were all about, why they thought we were great."

· The remastered edition of Dazzle Ships is out now on EMI